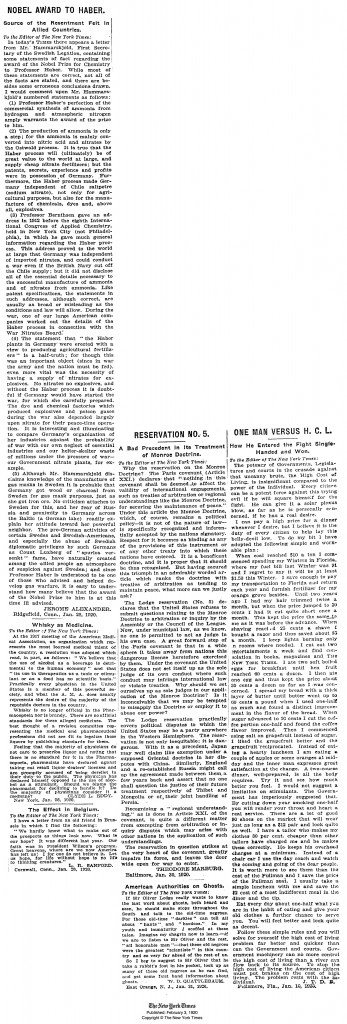

In 1918 Professor Fritz Haber was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for developing what is now known as the Haber Process. In 1920, an editorial piece in the New York Times was printed, which announces Haber’s Nobel win and discusses it in a modern context. The Haber Process allows Nitrogen to be extracted from the air and transformed into ammonia, a chemical that is important today for its use in fertilizers, but one that was even more crucial in 1918 at the end of World War I for its use in explosives. The article is a fascinating insight into what life was like during World War I, and how this piece of chemistry may have affected its outcome.

In 1918 Professor Fritz Haber was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for developing what is now known as the Haber Process. In 1920, an editorial piece in the New York Times was printed, which announces Haber’s Nobel win and discusses it in a modern context. The Haber Process allows Nitrogen to be extracted from the air and transformed into ammonia, a chemical that is important today for its use in fertilizers, but one that was even more crucial in 1918 at the end of World War I for its use in explosives. The article is a fascinating insight into what life was like during World War I, and how this piece of chemistry may have affected its outcome.

By 1920, Professor Haber had already received the nickname “the father of chemical warfare” for his development and deployment of chlorine and other poisonous gases during WWI. But, in 1918, ammonia was in high demand for explosives on the battlefield, and the N needed to produce it was hard to come by. Plain old air on Earth is made up of mostly nitrogen (78.1% to be exact), but the extremely strong triple bonds holding together the N molecules make it very hard to extract and essentially unavailable.

The Haber process uses high temperature (300-500 °C), high pressure (150-250 bars), and an iron or ruthenium catalyst to get the job done. It works so well, that the Haber process is still used today for ammonia synthesis.

Be the first to comment.